STRONG: What I’m Most Proud of in 2025

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

At the start of 2025, I chose STRONG as my word for the year.

I meant it quite literally. Physical strength. Energy. Stamina. The ability to keep going — in my body, in my days, and in the long stretches of work that don’t always show results immediately. I didn’t expect that word to surface so clearly in my painting practice, but looking back now, it’s impossible to separate the two.

The thing I’m most proud of this year isn’t a finished body of work, or even a single painting — although one painting, Shepherd in Canola, has come to hold a great deal of that meaning for me. What I’m proud of is a decision I didn’t rush. A moment where I trusted restraint over resolution, and allowed strength to look quieter than I expected.

The long avoidance of the figure

The truth is I'd been avoiding putting people into my paintings.

This wasn’t because I couldn’t draw — although figures do come with their own technical demands — but because I was wary of what they might do to the looseness I value so deeply in my work. I paint from feeling as much as from observation. I care about colour relationships, atmosphere, memory, and the way places are experienced rather than recorded. I worried that introducing a figure would pull the work toward stiffness, or toward explanation.

Figures ask questions.

Is it accurate enough?

Is it convincing?

Does it “work”?

And once those questions arrive, it’s very easy to start painting defensively. We’ve all seen it happen: the moment an artist feels the need to prove competence, the painting tightens. The story closes. The air goes out of it.

So I waited. Not deliberately, perhaps, but patiently — until one day, the presence of a figure felt necessary rather than threatening.

Letting the landscape produce the figure

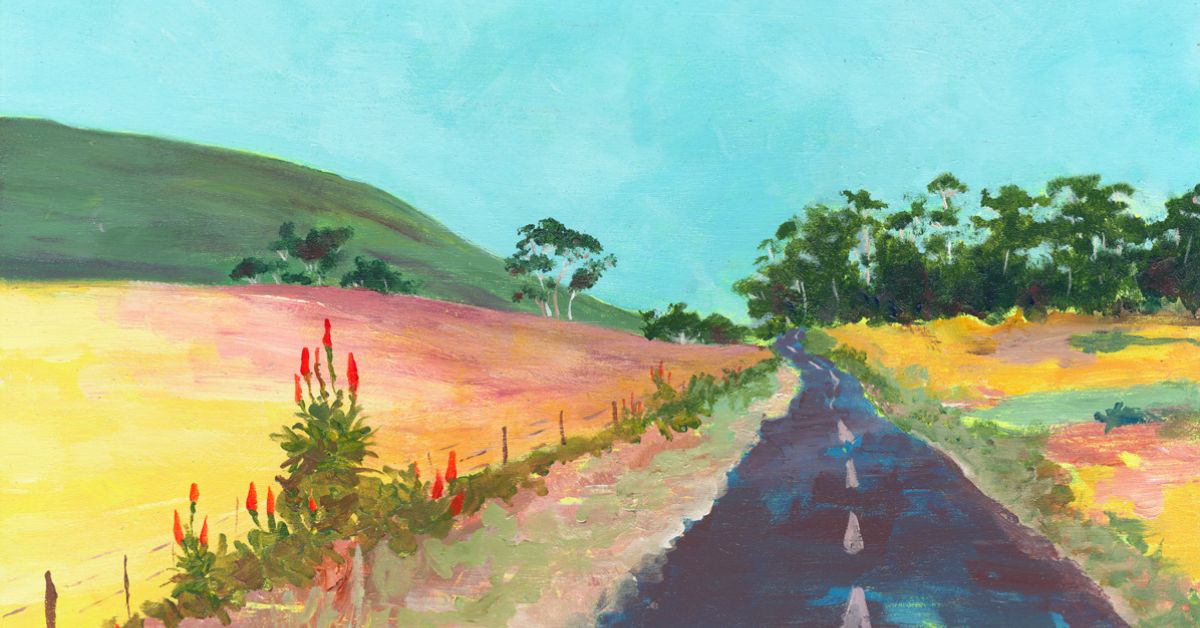

Shepherd in Canola didn’t begin as a “figure painting”.

It began, as so many of my works do, with land — with colour, movement, and the sensation of walking through a place. The yellow of canola fields is almost confrontational in its intensity. It vibrates against greens and blues. It flattens distance while simultaneously pulling you forward.

The figure entered the painting not as a subject, but as a presence — a way to introduce human rhythm into the landscape without dominating it. I am deeply interested in people as individuals, but I didn't want to impose my own interpretation of this man onto the viewer. I didn’t want to fix his identity through detail or specificity, or to burden him with my own assumptions, prejudices, or affirmations.

Instead, I wanted him to remain open enough to be inhabited.

For that reason, I resisted defining him too precisely. I wanted him to feel as though he could belong just as easily in the American Midwest, the fields of Eastern Europe, or anywhere people move quietly through working land. What mattered to me was not who he is in a biographical sense, but the feeling he carries — a sense of peace, attentiveness, and being at ease with the animals in his care and the land they roam.

In this way, the figure exists to locate the viewer rather than to explain the scene. He gives scale, movement, and human tempo to the landscape while leaving the story open, available for the viewer to complete in their own way.

The decision not to resolve

Once the figure was in place, the familiar tension arrived.

I could refine it.

Sharpen it.

Make it undeniably “good.”

There is comfort in clarity. There is reassurance in correctness. A well-rendered figure signals competence. But I knew that doing so would fundamentally change the painting. The more specific the figure became, the more it would dominate the story. What felt open would close.

It took more strength to stop than it would have to continue.

That’s something I’ve come to understand more deeply this year: restraint is not hesitation. Leaving something unresolved is not the same as failing to finish it. Often, it’s the point at which the work begins to belong to the viewer rather than the artist.

I didn’t want to paint the shepherd.

I wanted to leave space for a shepherd.

Redefining STRONG in the studio

This is where STRONG quietly shifted meaning for me.

Strength, in the studio, isn’t about control or polish. It’s not about tightening the work until nothing can be questioned. It’s about tolerating uncertainty — about trusting that suggestion can be enough, and that recognisability doesn’t require certainty.

It takes strength to resist the urge to prove yourself.

It takes strength to leave marks that breathe rather than explain.

It takes strength to believe that viewers are perceptive, emotionally literate, and capable of bringing their own stories to the work.

In Shepherd in Canola, the figure obeys the same rules as the landscape. It’s built from colour relationships rather than outline. It dissolves slightly into atmosphere. It participates in the painting rather than standing apart from it.

That decision felt like a quiet turning point in my practice.

Carrying this forward

I don’t see this painting as a conclusion, or as evidence that I’ve “solved” something.

If anything, it represents a permission — to allow figures to appear when they need to, without asking them to carry more meaning than they should. A permission to trust looseness even when the subject invites precision. A permission to let paintings remain porous.

Looking back on 2025, STRONG didn’t show up as force. It showed up as confidence without noise. As decisions made quietly and held firmly. As the understanding that not every story needs to be finished by the artist.

And that, more than any single outcome, is what I’m most proud of.

*Shepherd in Canola the original painting is sold, but the image is available as a greeting card as part of my Country Life and Landscape card collections.